Implications of Moscow-Beijing Axis for Indo-Russian Relations

© AP Photo / AP Photo/Manish Swarup, File

Subscribe

There are mounting Indian concerns that given the current crisis in Ukraine and Russia’s increasing closeness with China, Russian foreign policy towards India is being heavily influenced by Beijing's friendship with Moscow. Nothing could be further from the truth.

By Aaryaman Nijhawan*

It may be expedient to conclude straightaway that Moscow and Beijing’s historic alliance represents a direct threat to Indian-Russian relations.

A closer look would indicate that it’s not all moonlight and roses for the two non-Western giants. Lingering doubt, mistrust, and concern about the infringement of sovereignty overlap with power asymmetry and subtle Great Power competition over zones of influence.

It may be expedient to conclude straightaway that Moscow and Beijing’s historic alliance represents a direct threat to Indian-Russian relations.

A closer look would indicate that it’s not all moonlight and roses for the two non-Western giants. Lingering doubt, mistrust, and concern about the infringement of sovereignty overlap with power asymmetry and subtle Great Power competition over zones of influence.

True, many congruent fields of collaboration exist between Russia and China, and both states have capitalized on it. But assuming that such a relationship mean agreeing blindly to each other would be incorrect. In fact, it’s the opposite; both Moscow and Beijing are extremely sensitive about their sovereignty and territorial integrity. Both states are steadfast defenders of their national interests against what they see as the antagonistic dominance of the American-led liberal world order. Both possess negative historical experiences where sovereignty and national interest were compromised – for China, it was the “Century of Humiliation” and for Russia, it was in the immediate aftermath of the post-Cold War period.

Both states, sharing a deeply messianic civilizational mindset like the Americans, feel the dominant West did not give them equal respect and recognition in their liberal world order. As a result, both Moscow and Beijing are fiercely independent entities collaborating simply because it is beneficial for both of their national interests to do so. Since both value strategic autonomy their relationship is based on mutual respect and recognition. They share the same goal – the demise of the American-dominated liberal order, have similar concerns – non-recognition of their proper place on the global stage by the West, and similar mechanisms of remedying it – facilitating the emergence of a multipolar world order which gives them a stronger say in global engagements.

Values Defining Russian Foreign Engagement

Due to its core values of civilizational autonomy, independent foreign policy, and decision-making, it is unlikely that Beijing’s stance or advice would have a major say in Russian relations with India.

Two major reasons support this claim:

Two major reasons support this claim:

Firstly, Moscow is acutely aware that the Sino-Russian relationship is an alliance of opportunity. In stark contrast, the Indo-Russian partnership is marked with “sympathy, trust and openness” at an unprecedented level that Russia rarely shares with any other state in the world. Given India’s resurgent status, its autonomous foreign policy strategy that Russia highly respects, and as a balancer between the East and West, it is clear that the Russians view India as a serious and respected ally. It is worth noting that during the Cold War, the USSR implored the PRC to follow a more moderate stance towards India but the latter refused, partly due to surging tensions between China and the Soviet Union leading up to the infamous Sino-Soviet Split. One of the primary reasons for the split was the Soviet unwillingness to support China (a ‘brother’) against India (a ‘friend’).

Second, Russia is aware of the asymmetric power dynamic with China and is evidently skeptical of Chinese plans for expansions in the Arctic – an area that Russia considers its backyard.

Within its official documents, namely the Foreign Policy Concept of the Russian Federation 2023 and Basic Principles of Russian Federation State Policy in the Arctic to 2035, Moscow has used terminology that “is designed to defend the national interests of the Russian Federation in the Arctic.” The documents clearly mention that “developing the Northern Sea Route as the Russian Federation’s competitive national transportation passage in the world market” is a national priority with challenges mentioned as “attempts by a number of foreign states to revise the basic provisions of the international treaties governing economic and other activities in the Arctic.”

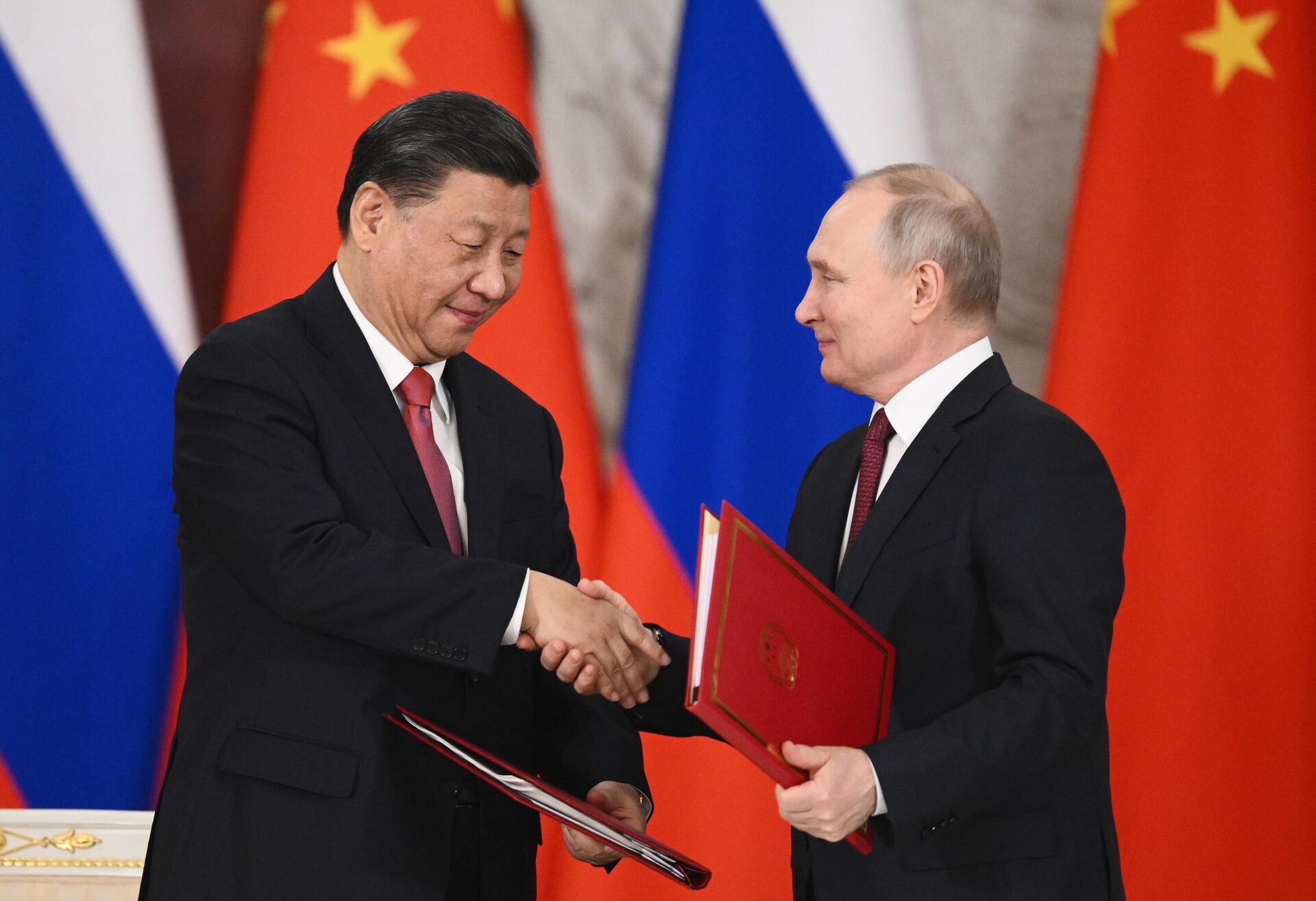

Chinese Leader Xi Jinping and Russian President Vladimir Putin shake hands after signing a joint statement on deepening comprehensive partnership and strategic cooperation and on the plan for development of key areas of the economic cooperation until 2030 at the Kremlin, in Moscow, Russia.

© Sputnik / Mikhail Tereshchenko

/ Conflicting Spheres of Influence

While Moscow would prefer for India and China to settle their differences, there are certain border controversies between Moscow and Beijing (a good reason why India and China are still unable to resolve their own), including incorrect maps of the places along the Sino-Russian border published by the Chinese authorities.

While the Chinese economy has grown into an economic powerhouse, its search for new markets has clashed with the traditional Russian sphere of influence. Contemporary Central Asian geopolitics appear to be headed the same way as Europe’s; politically integrated with Russia but more economically integrated with China. However, both Moscow and Beijing are currently focusing on coexistence and cooperation rather than exclusion and geopolitical confrontation. In accordance with realpolitik, in May 2015 China and Russia announced the cooperation between the Chinese-led Silk Road Economic Belt (SREB) and the Russian-led Eurasian Economic Union (EAEU) in the Central Asian region.

For the time being, due to the conflict in Europe and Russia's necessity for a Chinese economic parachute, Moscow isn’t showing any unease, at least in public, towards Chinese incursions within its traditional spheres of influence. After all, Russia is sensitive about its own Great Power status and maintenance of its spheres of influence which was the root cause of the escalation of the Ukrainian conflict.

Collaboration with West

As of 2023, both India and China are more economically integrated with the West than Russia. However, although Beijing conducts a significant amount of its trade with the US and Europe in contrast with Russia, the United States is also its main adversary in terms of ushering in a more multipolar world order.

India’s increasing ties with the US and Russia’s closeness to China have undeniably complicated relations between the two all-weather friends. India started inking major defense investments with the United States while Russia moved to lift its self-imposed arms embargo on Pakistan in 2014. However, it is possible that if a major conflict escalates between India and China, Russia will more likely play a neutral role. On the other hand, Indian strategic analysts believe that if push comes to shove, Washington won’t hesitate to enter a proxy conflict against China.

Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi welcomes U.S. President Joe Biden upon his arrival at Bharat Mandapam

© AP Photo / Evan Vucci

Implications for India

The outbreak of the Ukrainian conflict has certainly changed the dynamics of Russia’s relations with both India and China. With China, it has led to deeper Russian economic dependency in light of Western sanctions and greater military partnership between the two nations.

But it would be a fallacy for India to view it as a zero-sum game. India engages with both Russia and China bilaterally and multilaterally through platforms such as the Russia-India-China (RIC) grouping, the Shanghai Cooperation Organisation (SCO), and the Brazil, Russia, India China, and South Africa (BRICS) grouping which was recently expanded to BRICS+. For Russia, India is also conversely a vital balancing partner in offsetting the asymmetric power dynamics it possesses with China.

Another positive aspect is that due to geographical distance Russia and India never had any border disputes, unlike their separate relationships with China. Beijing and Moscow don’t stand shoulder-to-shoulder on all issues including the Arctic region with China’s own Polar Silk Road ambitions and the still inconvenient border issues that crop up from time to time. Furthermore, Russia still readily supports India whenever the West won’t in terms of technology transfer in arms deals and building indigenous nuclear submarines – a prominent reminder of why India still needs Russia without being overdependent on American armaments.

Finally, all three powers – Russia, India and China – seriously value sovereignty, strategic autonomy, and independence in policy decision-making. These provide sufficient grounds to conclude that despite the much-touted Russian-Chinese honeymoon, Moscow will still remain India’s faithful partner in the multipolar times to come.

*Aaryaman Nijhawan is an International Relations researcher and political commentator. He is a graduate of University of Delhi, India and Moscow State Institute of International Relations (MGIMO University), Russian Federation.